| Jazz |

Some Records Are Better Left Unreviewed. Unfortunately, This Isn’t One of Them.

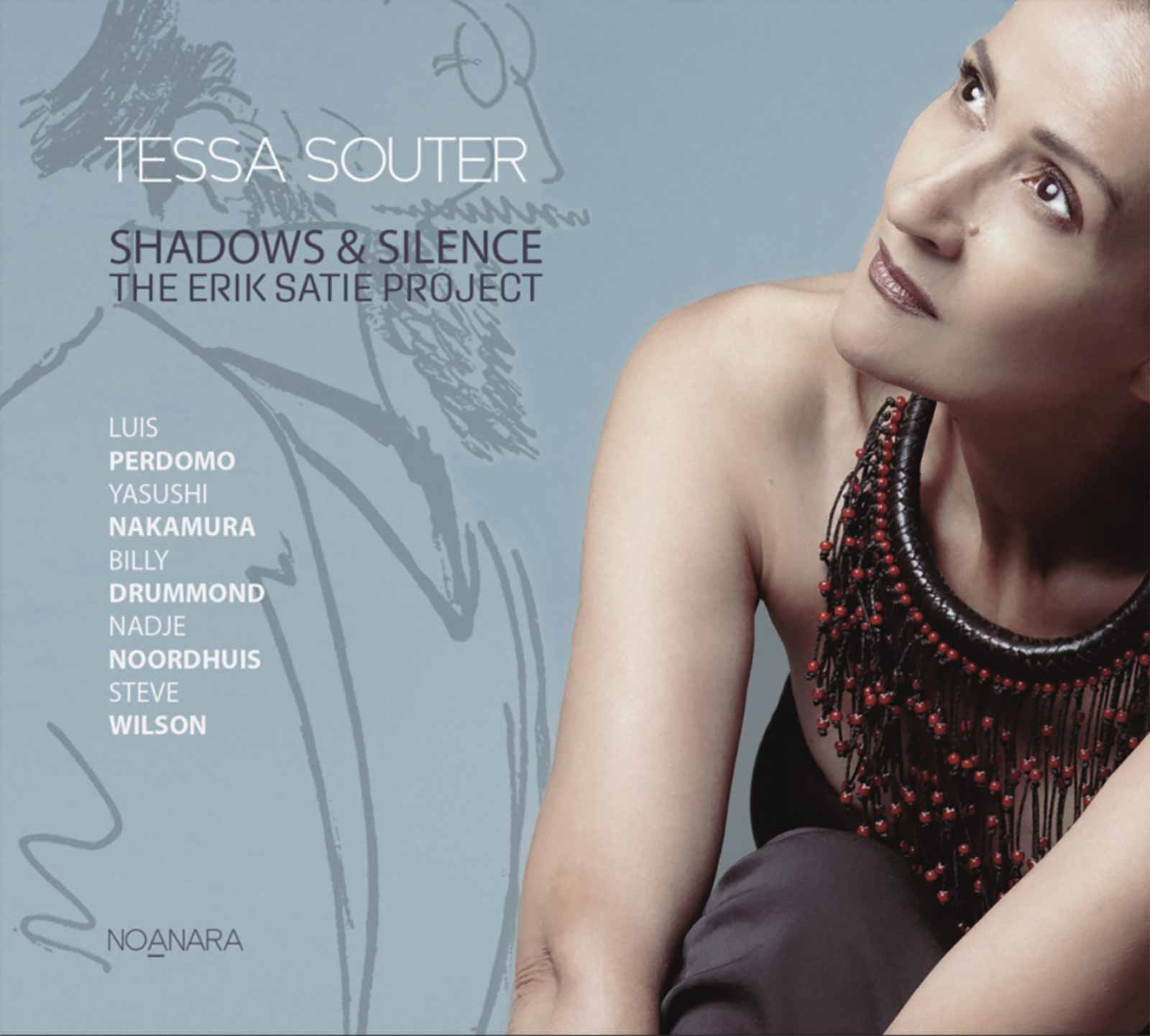

Every so often, a record crosses a critic’s desk that provokes not admiration, curiosity, or even distaste, but something altogether more complex: reluctance. A desire, even, to look away. Not because the music is aggressively bad, although that, too, may apply, but because what it attempts is so misaligned with its raw materials, so blind to the spirit of what it touches, that addressing it becomes an exercise in frustration. This album, sadly, falls squarely into that category.

It is a work that attempts to conjure the ghost of Erik Satie, one of France’s most enigmatic and delicately innovative composers, and in doing so, stumbles not into homage but into confusion. It also seeks to borrow the poetic gravitas of chanson giants like Léo Ferré and Jacques Brel. But rather than drawing from the profound emotional well that runs beneath those songs, it skims their surfaces like a tourist repeating foreign phrases without understanding their meaning.

Satie’s compositions, particularly the Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes, are pieces of almost metaphysical minimalism: airy yet filled with the weight of unspoken sorrow, as if the music is always trailing the shadow of a memory it dares not name. Interpreting Satie, especially within a jazz framework, is not impossible, and indeed, some have done so with grace, intelligence, and imagination. What is required is a sense of restraint, a sensitivity to nuance, and above all, humility. Here, however, the listener is treated to a curious act of bravado masquerading as tribute.

The album opens with a rendition that immediately sets the tone: a murky, almost indecipherable passage of French spoken over a fractured instrumental backdrop. It is a choice that feels more accidental than experimental, an uncanny simulation of Frenchness, as imagined by someone with no apparent connection to the language. For those of us who speak French, the linguistic missteps are not just distracting, they are disorienting. One cannot help but wonder how this was allowed to pass through the hands of a producer, an editor, or even a studio intern without intervention.

As the album continues, the strangeness only deepens. The choice to cover Léo Ferré is ambitious, but perhaps not in the way the artist intended. Ferré’s work demands a level of interpretive sophistication rarely found outside his native cultural sphere. His songs are thick with existential despair, anarchic poetry, and a kind of weary romanticism that does not yield easily to translation, musical or otherwise. Having once had the rare privilege of rehearsing with Ferré—singing Avec le Temps with him in a quiet moment of camaraderie—I can testify to the emotional density that lies beneath the surface of those seemingly simple lines. What we hear on this album, instead, is a phonetically rendered performance devoid of internal compass. The words are sung, but they are not inhabited.

The same is true of the album’s rendition of Ne Me Quitte Pas, a song that has been interpreted by many and mastered by few. Jacques Brel did not write it as a ballad of sweet longing. It is a plea, a lament, a song that bleeds from the voice. It should unsettle you. It should break something open. But here, it is delivered with the emotional resonance of a karaoke performance, technically competent, perhaps, but emotionally hollow. By the end of the track, I found myself sitting in silence, not out of awe, but from a kind of stunned sadness. Not sadness evoked by the song, but by the performance itself, and the realization that something sacred had been mishandled.

The album is not entirely without its merits. The instrumentalists, whose names I will refrain from listing here out of mercy, are clearly of the highest caliber. Their phrasing is elegant, their tonal choices refined, and their improvisations tasteful. Again and again, one senses that they are doing their utmost to elevate the project, to anchor it in musical legitimacy. But even their most inspired efforts cannot compensate for the fundamental flaws of the record’s concept or its vocal execution.

Tracks like ESP, an ambitious choice, drawn from Miles Davis’s more abstract period, are stripped of their tension and intelligence, transformed into atmospheric wallpaper. And then there is Never Broken, a piece once rendered with aching beauty by Cassandra Wilson, here reduced to a series of gestures that feel oddly disconnected from the song’s emotional DNA. One begins to suspect that the artist is performing from a script rather than from within.

As fatigue began to set in, I reached for a final act of generosity: I queued up Rauga’s Song, loosely inspired by Gymnopédie No. 1, in hopes of discovering a moment of clarity or coherence. It did not come. Once again, the musicians provide a lush and thoughtful sonic palette, but the vocal performance once again veers into a territory that is not simply unconvincing, it is alienating.

There is an emerging trend in modern jazz and crossover projects that leans heavily on eclecticism for its own sake. Genre-fusion, multilingualism, cultural reference—these are not inherently problematic tools. But when they are employed without care, without understanding, and without the humility to know when to step back and listen, they become weapons. They distort rather than illuminate. And worst of all, they betray the very traditions they seek to honor.

This album, in its attempt to blend Satie’s fragile impressionism with the brooding poetry of French chanson and the spacious improvisation of jazz, collapses under the weight of its own ambition. It does not reinterpret. It disassembles. It does not translate. It misrepresents.

There may be listeners for whom none of this matters, those who come to the album without knowledge of Satie, of Brel, of Ferré, or of the French language itself. For them, perhaps, this recording will pass as ethereal or adventurous. But for those of us who have lived with this music, who know what it can do when it is treated with care and reverence, the experience is not just disappointing, it is disheartening.

And so, reluctantly, this review must exist. Not because the album deserves our attention, but because the music it draws from does. Silence, in this case, would feel too much like complicity.

Thierry De Clemensat

Member at Jazz Journalists Association

USA correspondent for Paris-Move and ABS magazine

Editor in chief – Bayou Blue Radio, Bayou Blue News

PARIS-MOVE, May 28th 2025

Follow PARIS-MOVE on X

::::::::::::::::::::::::

Musicians:

Tessa Souter – vocals/ lyrics/ arrangements

Luis Perdomo – piano/ percussion/ arrangements

Yasushi Nakamura – bass

Billy Drummond – drums and cymbals /arrangement of track 6

Nadje Noordhuis – trumpet and flugelhorn

Steve Wilson – soprano saxophone

Pascal Borderies – spoken word

Tracklist :

A song For You (Gnossienne No.1)

Mood (Musica Universallis)

Yasushi

Holding on to Beaty (Gnossienne No.3)

Avec le Temps (Léo Ferré)

D’ou Venons Nous (Gymnopedie No.3)

Vexations (I Kiss You Heart)

Never Broken (ESP)

Rayga’s Song (Gymnopedie No.1)

If You Go Away/ Ne me Quitte Pas (Jacques Brel)