| Jazz |

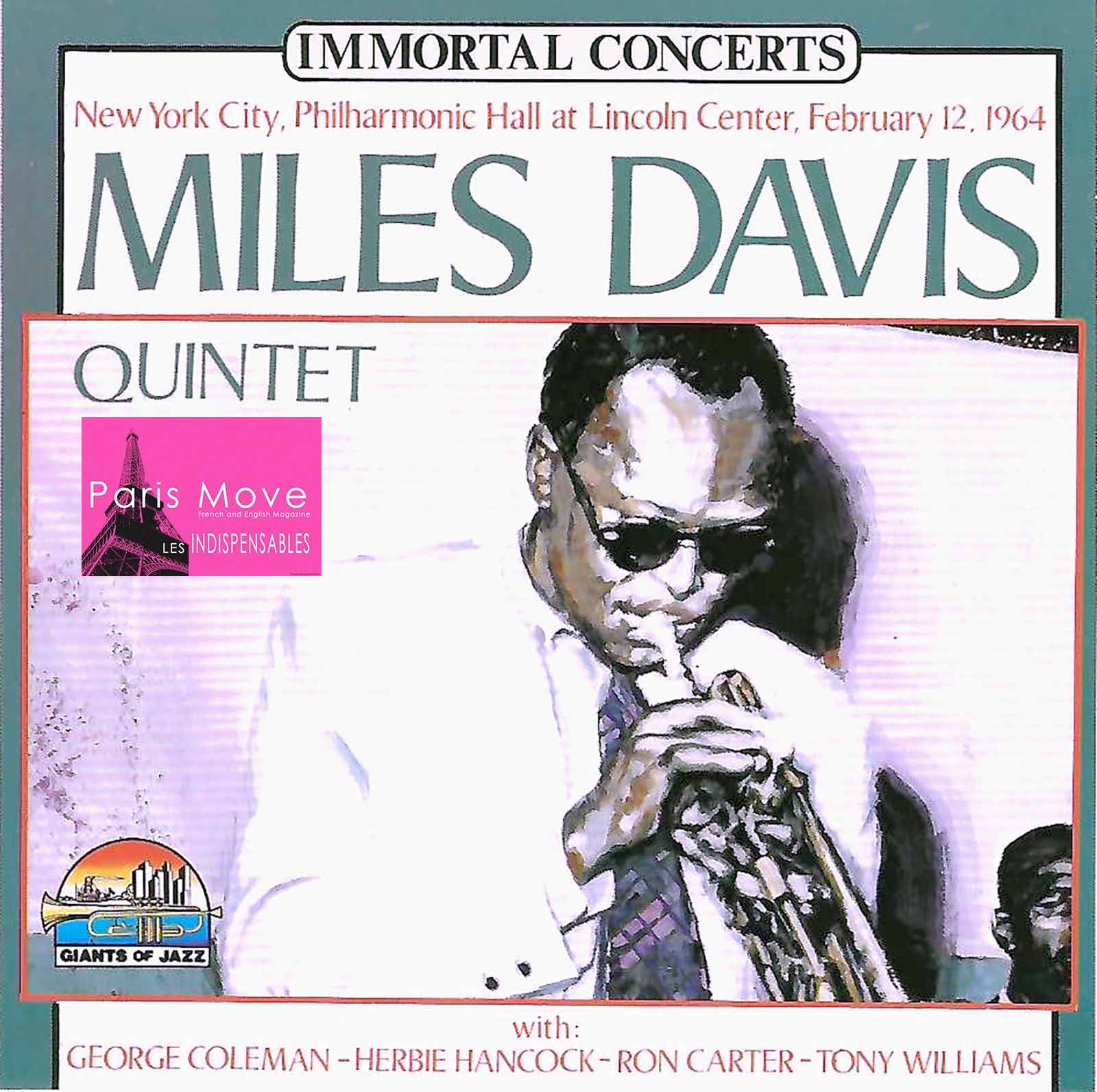

At Bayou Blue Radio, jazz memory functions less like an archive than a form of vigilance. It is a constant alertness to the objects, records, sleeves, liner notes, forgotten pressings, that quietly shaped the music’s history. This vigilance often leads, quite literally, to chance encounters. One of them occurred in a second-hand CD shop, one of those places where time collapses and hierarchy dissolves, where masterpieces sit beside obscurities in anonymous plastic bins. There, wrapped in the plainest of sleeves, was an album by a brilliant trumpeter presenting what was, in fact, his second great quintet, though at the time of its recording, I would have been blissfully unaware of any of this, being barely four years old.

The album has since become nearly impossible to find. It has never been reissued, never properly contextualized, yet it was recorded on a date saturated with historical meaning. Just three weeks earlier, the 24th Amendment to the United States Constitution had been ratified, formally abolishing poll taxes as a condition for voting. It was a turning point in American democracy, one that unfolded alongside the fervor of Freedom Summer and culminated, that same July, in the signing of the Civil Rights Act by President Lyndon B. Johnson. This is not incidental background. It is the political and moral atmosphere in which this music was conceived, performed, and received.

The album radiates a particular kind of energy, expressive, urgent, almost combustible. There is a sense of release in the playing, perhaps even of victory. The audience, audible throughout, responds with an intensity that feels unusually charged, as if fully aware that this was more than an evening of entertainment. This record was, in fact, one of only two similar albums produced during that brief period. The concerts themselves were organized in support of the Voter Education Project, a cornerstone initiative of the civil rights movement aimed at expanding Black voter registration in the American South.

For jazz musicians of that era, political engagement was not an abstract stance but a lived necessity. Miles Davis, in particular, understood the symbolic power he carried. To attract wealthy donors to these benefit concerts, he reportedly sent invitations printed on his own personal letterhead, a subtle but effective strategy that all but guaranteed packed rooms and generous contributions. Miles was not merely lending his name; he was placing his reputation, his image, and his art in direct service of the cause. Onstage, he pushed himself further than usual, transforming these performances into statements of both artistic mastery and civic resolve. This dual commitment, to music and to justice, became inseparable from his public identity and from the enduring depth of his work.

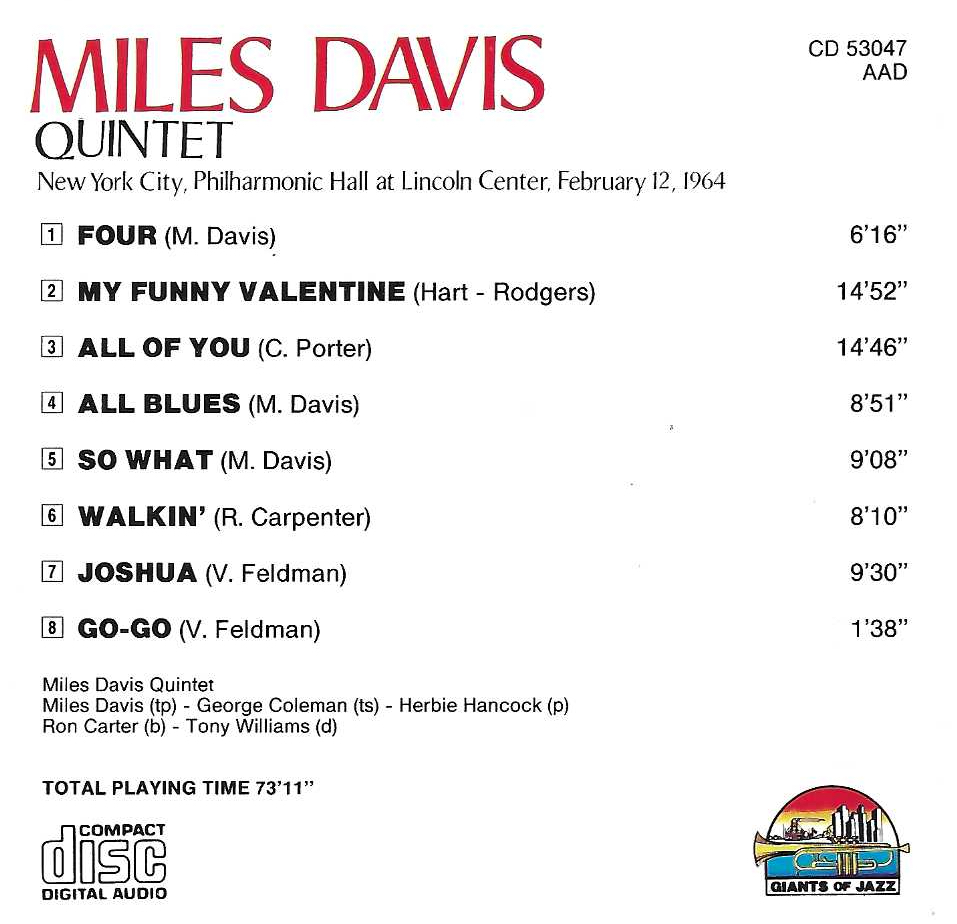

The quintet assembled for this recording was nothing short of extraordinary. Alongside Miles Davis stood George Coleman on tenor saxophone, Herbie Hancock at the piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums. It was a configuration destined for greatness, a convergence of intellect, virtuosity, and generational renewal. The chemistry is immediate, the dialogue constant, the sense of collective purpose unmistakable.

Years later, I would see Miles Davis again, this time in France, in the early 1980s. By then, his approach had radically changed. Onstage, he played sparingly, sometimes offering only a few essential notes before retreating into silence. Yet his presence was overwhelming. This was stardom in its purest form, the kind that cannot be engineered by marketing departments or social media strategies. True stardom is forged by history, by risk, by endurance. Everything about Miles was exceptional: the way he played, the way he looked at his fellow musicians, the grain of his voice when he addressed the audience.

The contrast between these two Miles Davises, the expansive, almost loquacious trumpeter of the 1960s and the minimalist icon of the 1980s, only deepens the meaning of his legacy. In the earlier period, his trumpet seemed incapable of restraint, pouring out ideas with relentless urgency. In the later years, silence became part of the music. Both phases were equally radical, equally modern.

To listen to Miles Davis is not simply to encounter some of the most forward-looking music ever produced, regardless of era. It is to step into a moment where musical innovation intersects with social struggle and political transformation. Jazz, at its core, is an art of nonconformity, and Miles embodied that principle more fully than perhaps any other figure in its history.

I recall one particular moment vividly. Miles announced “So What” into the small microphone attached to his trumpet. What followed, according to the timer on my camera, were two uninterrupted minutes of screams and applause. During that wall of sound, he had already begun to play. Only a handful of notes managed to rise above the roar. I have never witnessed anything comparable with another jazz musician. Some individuals simply exist above the mêlée, carried by lives so improbable they verge on myth.

Miles Davis’s journey, from profound suffering to the brightest stages in the world—was anything but predetermined. The wager placed on him at birth would not have seemed a winning one. And yet, he became one of the most deeply loved figures in jazz history. Decades after his death, we continue to speak of him with undiminished admiration, for the man as much as for the artist.

At Bayou Blue Radio, records like this are more than programming material. They are reminders that jazz is not only a musical language but a historical testimony. Each broadcast is an act of transmission, not just of sound, but of memory, where the history of jazz, the struggle for civil rights, and the broader American story converge once again, note by note, across time.

Thierry De Clemensat

Member at Jazz Journalists Association

USA correspondent for Paris-Move and ABS magazine

Editor in chief – Bayou Blue Radio, Bayou Blue News

PARIS-MOVE, December 14th 2025

Follow PARIS-MOVE on X

::::::::::::::::::::::::

To Buy This album: Album not reissued

Musicians :

Miles Davis (Trumpet)

George Coleman (Tenor saxophone)

Herbie Hancock (Piano)

Ron Carter (Double Bass),

Tony Williams (Drum)

Tracklisting :

Four [Live]

My Funny Valentine [Live]

All Of You [Live]

All Blues [Live]

So What [Live]

Walkin’ [Live]

Joshua [Live]

Go-Go [Live]