| Jazz |

There are albums whose lyricism asserts itself from the very first notes, records that seem to arrive not through the slow, deliberate machinery of the music world but as meteorites, self-contained, radiant, and puzzling. Zanzibar, the forthcoming release from the French duo Bec & Ongles—pianist François de Larrard and drummer Mathieu Bec, is one of those rare apparitions. It does not ask permission to exist; it simply descends, unclassifiable and unmistakably whole.

In today’s increasingly codified jazz landscape, where genres fracture into micro-currents and listeners seek comfort in playlists promising “focus”, “chill”, or “vibes”, an album like Zanzibar feels almost defiant. It insists on attention. It insists on dialogue. And above all, it insists on the idea that music is not a destination but an ongoing negotiation between two sensibilities. De Larrard and Bec approach their craft like sculptors working a single block of sound, chiseling, pressing, resisting, yielding. The line between composition and improvisation becomes permeable, shifting like a dune in wind.

Two Portraits, One Language

François de Larrard is, on paper, a classically trained pianist, rooted in counterpoint, harmonic logic, the architecture of form. But nothing in his playing here feels bound by tradition. Instead, those classical foundations become a springboard into zones where Satie brushes against minimalism, where jazz phrasing slides into chamber-music restraint, where suggestion matters more than display. His melodies often feel like aftermath, what remains after a thought has already evaporated.

Mathieu Bec, by contrast, is a rhythmic shapeshifter. His relationship to African rhythmic traditions is neither ornamental nor borrowed; it’s absorbed, metabolized, and reimagined. At times he constructs entire ecosystems from a single pulse; at others, he seems to borrow silence from the pianist and return it transformed. He is not a timekeeper but a co-architect, carving temporal pathways through which de Larrard threads his lines. The empathy between them is startling, less dialogue than shared cognition, as if each were finishing the other’s sentences.

Music That Thinks, Music That Dreams

Listening to “The Life of a Man”, the album’s emotional fulcrum, one hears echoes of Satie, not the genteel salon composer of cliché, but the subversive figure whose music carried a quiet revolutionary force. The piece unfolds like an Escher drawing made audible: recursive, questioning, curving back on itself. One does not simply hear it; one inhabits it.

The track, like others on the album, rests on an ostinato, a musical device so ancient it predates harmony itself. In the hands of Bec & Ongles, the ostinato becomes more than a pattern; it becomes a metaphor for human persistence. These loops recur not as repetition but as evolution, shifting subtly, acquiring patina, reacting to the musicians’ impulses. They are mantras, incantations, the ground on which the duo builds their fragile but resilient architectures.

The two excerpts from the Zoo suite follow similar principles. Their circularity feels almost primordial, as though improvisation were being rediscovered anew. Between these pulses emerge sudden free outbursts, lyrical detours, and quiet meditations suspended in air. Nothing is fixed. Everything circulates. The music breathes with the organics of conversation, its hesitations, its accelerations, its unexpected digressions.

Silence as a Third Musician

Underlying the entire album is a profound understanding of silence. Not as absence, but as force. These musicians write with silence the way writers use punctuation—creating tension, expectation, surprise. The spaces between notes carry as much meaning as the phrases themselves. In an era when many recordings chase saturation and density, Zanzibar reclaims the value of spareness. Its restraint becomes its power.

And yet the music never slips into abstraction for its own sake. Even when it brushes dissonance, it does so with intention, like testing the integrity of a surface. The album maintains a delicate equilibrium between clarity and mystery, structure and risk. It is music that resists easy categorization: too orchestrated to be free jazz, too exploratory to be classical, too textural to be traditional piano-percussion jazz, yet deeply rooted in all three.

Why This Album Matters Now

Piano-drum duos are rare in modern jazz. They expose everything, there is nowhere to hide, no harmonic lattice or bass foundation to lean on. For this reason alone, Zanzibar feels both bold and generous, offering the listener access to the very mechanics of musical thought. But the album also resonates within a wider cultural moment where boundaries, between styles, between art and research, between tradition and experiment, are dissolving.

In this sense, de Larrard and Bec belong to a new generation of artists for whom creation is not about aligning with a genre but about inventing a grammar. They map what tomorrow’s music might sound like: hybrid, porous, attentive, interdisciplinary. Their admiration for one another is audible in every track, not as sentiment but as method. The music is the by-product of trust.

The Experience of Listening

Hearing Zanzibar feels a bit like entering a room that is already mid-conversation. There is no exposition, no preface. The listener is invited, gently but firmly, into a sonic universe already in motion. The album demands presence. And that demand, in a world of sonic distraction, is radical.

Across its fourteen tracks, the record unfolds like a sequence of private rituals:

– the lyrical introspection of Emma’s Song,

– the kinetic architecture of Zanzibar,

– the playful tensions of Scherzophrenia,

– the fragile tenderness of Comptine pour Antónia,

– the urban shadows of Urbex,

– the farewell-lit softness of Peaceful Rondo.

Each piece functions as a fragment of a larger mosaic, separate, evolving images that ultimately resolve into a coherent whole, much like memory itself.

A Final Note

There are far too few albums capable of speaking to classical musicians and jazz improvisers with equal conviction, capable of plunging listeners into a world without warning, capable of forcing us, as gently or as firmly as needed, into a deeper form of listening. Zanzibar is one of them. It tastes like a long-aged vintage, one that reveals its subtleties gradually, offering new contours at each encounter.

In an age of disposable noise, Bec & Ongles offer something far rarer: music that listens back.

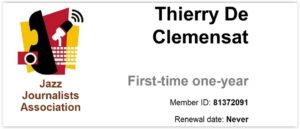

Thierry De Clemensat

Member at Jazz Journalists Association

USA correspondent for Paris-Move and ABS magazine

Editor in chief – Bayou Blue Radio, Bayou Blue News

PARIS-MOVE, November 26th 2025

Follow PARIS-MOVE on X

::::::::::::::::::::::::

Musicians :

François De Larrard, piano

Mathieu Bec, drums

Track Listing :

1 Emma’s song (05’36)

2 Zoo 6 (04’11)

3 The life of a man (08’34)

4 Andante (02’49)

5 Zanzibar (05’29)

6 Comptine pour Antónia (04’53)

7 Scherzophrenia (03’52)

8 Urbex (04’19)

9 Zoo 7* (03’01)

10 Valse à cloche-pied (04’18)

11 Pense-bête (03’55)

12 Amistad (01’39)

13 Offrande (04’07)

14 Peaceful rondo (05’48)