Rob Reiner, or the quiet humanism of American cinema

By Thierry De Clemensat

Member at Jazz Journalists Association

USA correspondent for Paris-Move and ABS magazine

Editor in chief – Bayou Blue Radio

December 17th 2025

Some deaths arrive softly, like a final fade-out. Others strike with the brutality of a hard cut. The passing of Rob Reiner belongs unmistakably to the latter. A legend of American cinema is gone, tragically, abruptly, and with him disappears a certain idea of filmmaking: one rooted not in spectacle for its own sake, but in humanity, intelligence, and trust in the audience.

I remember the year 1986 vividly. I was still in Europe, and like many cinephiles of that era, I went to great lengths to find a theater willing to screen Stand by Me in its original version, subtitled. It was not an easy task at the time; original-language screenings were still a rarity. When I finally saw the film, it felt like a revelation. Not because of its plot alone, but because of its writing, its tone, its restraint, its emotional precision. It was, unmistakably, an auteur film disguised as a mainstream production. A large-budget film, yes, but one that never lost sight of the intimacy of its story.

There are films, like certain books, that quietly alter your inner compass. They do not announce their importance loudly; they simply settle into you and stay. Stand by Me was one of those works. It spoke of childhood, of friendship, of loss, and of that fleeting moment when innocence slips away forever. Rob Reiner understood something essential: that nostalgia, when handled with honesty, can illuminate rather than obscure truth.

Reiner was among a generation of directors whose careers I followed closely, alongside Steven Spielberg and others who embraced genre cinema not as limitation but as opportunity. These were filmmakers who took positions, who dared to ask questions, who used humor not as an escape but as a tool for reflection. Then came When Harry Met Sally. Once again, Rob Reiner delivered a film that would enter the collective consciousness. Entire scenes became cultural shorthand, endlessly quoted across continents. The famous diner scene is known even to those who have never seen the film. That kind of universality does not happen by accident.

The reason was simple: Rob Reiner placed humanity at the center of everything he made. Whether directing romantic comedies or confronting America with its own moral failures, as he did in Ghosts of Mississippi, he never condescended to his audience. His films trusted viewers to feel, to think, to wrestle with complexity. They were warm, but never simplistic; accessible, yet never shallow.

In time, as is often the case, his complete filmography will almost certainly be gathered into carefully curated box sets. Such retrospectives will remind us that Reiner was not only a major director, but also an extraordinary director of actors. He knew how to draw out performances that felt natural, unforced, deeply human. That ability requires more than technical skill; it demands empathy, patience, and a genuine love for people. Great directors understand cameras. Exceptional ones understand souls.

It is a cruel irony that it often takes the death of a man of this caliber for us to fully realize how thoroughly his work accompanied our lives. There was a quiet reassurance in going to see a Rob Reiner film. You knew you would not be disappointed, not because the film would always be comfortable, but because it would always be honest.

What no one was prepared for, however, was the manner in which his name would reappear, alongside his wife’s, in the crime pages. The shock was profound, the sadness overwhelming. Let us, however, leave that family tragedy where it belongs: in the realm of private grief. It robs us not only of the man himself, but of all the stories he might still have told, of all the ways he might have continued to remind us of our shared humanity.

Too often overlooked is the fact that Rob Reiner was also a fine actor. His performance as Izzy Rosenblatt in Primary Colors remains particularly touching, subtle, intelligent, and deeply felt. It was another reminder that his understanding of cinema extended far beyond the director’s chair.

Rob Reiner leaves behind an image that is rare in the modern media landscape: that of a man whose guiding principle was discretion. He appeared in the press not to cultivate celebrity, but to speak about his work, about storytelling, and about his love for the craft. He was neither loud nor self-promotional. His films spoke for him.

Yes, his passing leaves an emptiness. But what endures, what truly matters, is what he gave us. The films remain. The emotions remain. The sense that cinema, at its best, can be an act of kindness remains. And in that sense, Rob Reiner is not merely remembered. He endures, an exceptional figure, now part of eternity.

::::::::::::::

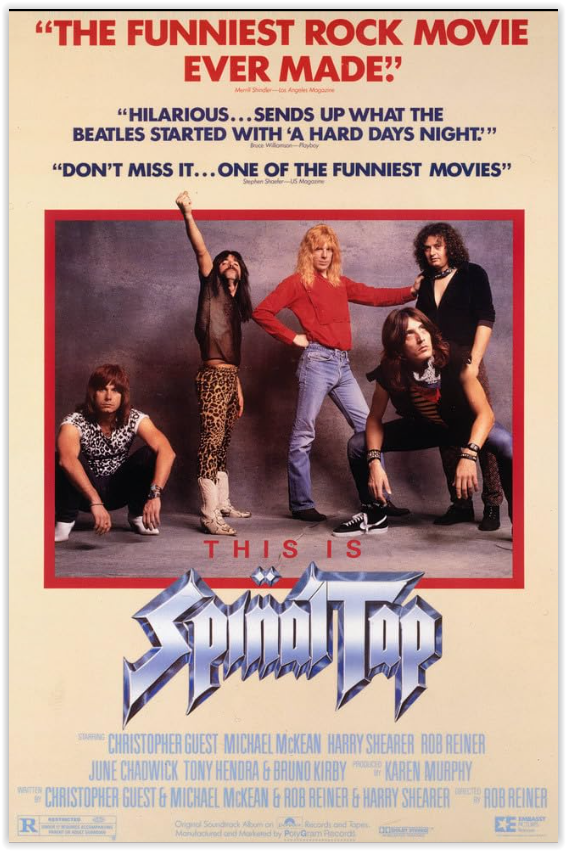

Selected by Paris-Move: This Is Spinal Tap (1984) directed by Rob Reiner.

“Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, and Harry Shearer play members of the fictional heavy metal band Spinal Tap. Reiner plays Martin “Marty” Di Bergi, a documentary filmmaker following the band’s American tour. The film satirizes the behavior and musical pretensions of rock bands and the hagiographic tendencies of rock documentaries such as The Song Remains the Same (1976) and The Last Waltz (1978), similarly to what All You Need Is Cash (1978) by the Rutles did for the Beatles. Reiner, Guest, McKean, and Shearer wrote the screenplay, though most of the dialogue was improvised and dozens of hours were filmed.

This Is Spinal Tap was released to critical acclaim, but found only modest commercial success in theaters. Its later VHS release brought greater success and a cult following. Credited with “effectively” launching the mockumentary genre, it is also notable as the origin of the phrase “up to eleven”. Deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress, it was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2002. Reiner, Guest, McKean, and Shearer reprised their roles for the 2025 sequel Spinal Tap II: The End Continues and the 2026 concert film Spinal Tap at Stonehenge: The Final Finale.” (Wikipedia page)

Added by the Editor-in-chief of Paris Move, Frankie Pfeiffer

Follow PARIS-MOVE on X