Of course, as always, a thousand ideas swirled in my mind for an editorial, but then came this suggestion from my friend Jay Myers—to write about this month dedicated to the history of Black Americans.

As a white Frenchman, I felt no legitimacy to speak of a history so painful and harrowing, especially since, in France, one would be hard-pressed to find anyone who openly acknowledges descending from a family of enslaved people. And yet, France, too, was a colonizing power, a nation that participated in slavery. The archives, for the most part, vanished during the Revolution, and even today, it remains an uneasy topic, rarely broached in polite conversation. Though the city of Nantes has dared to acknowledge its sinister past as a hub of the slave trade, erecting a monument as a testament to that grim history, the broader reckoning is still wanting.

But Jay said to me, “You can speak of jazz, of what Black music means to you.” And at that, my face lit up. I was transported back to my earliest childhood—no taller than three apples high—on a Christmas Eve. The tree twinkled, and on the black-and-white television, a holiday program began. There were only two channels in those days, and you can imagine the wide-eyed wonder of a child watching a Black man pour his entire soul into a trumpet, filling the room with sounds that thrilled me beyond words. It was Louis Armstrong, resplendent as a prince in his evening suit. Beside him stood a woman, also Black, with a voice so exquisite it seemed to float, pronouncing words I could not yet understand. That was Ella Fitzgerald, dressed in what, to my young mind, could only be a “princess gown”—a shimmering, sequined dress, the kind that only true royalty could wear with such grace.

The years passed, and Louis and Ella remained a fixture of my festive celebrations. Then came another figure to enchant my ears and eyes—a certain Ray, with dark glasses and a piano beneath his fingers, his voice an instrument in itself. Ray Charles, whom I adored then and adore still. A little older, I entered the conservatory: solfège, classical training, the cello. But deep inside, it was jazz that called to me. Rhythm and blues beckoned. I turned to the saxophone and soon encountered Sonny Rollins—a revelation, an artistic and emotional shock. I advanced in my studies, but at that time, I found no one to share in the music I loved. No matter—I persisted. Miles Davis, Ron Carter, Marcus Miller, Earth, Wind & Fire…

None of my idols, curiously, shared my skin color. Yet, their music was the only language I truly understood.

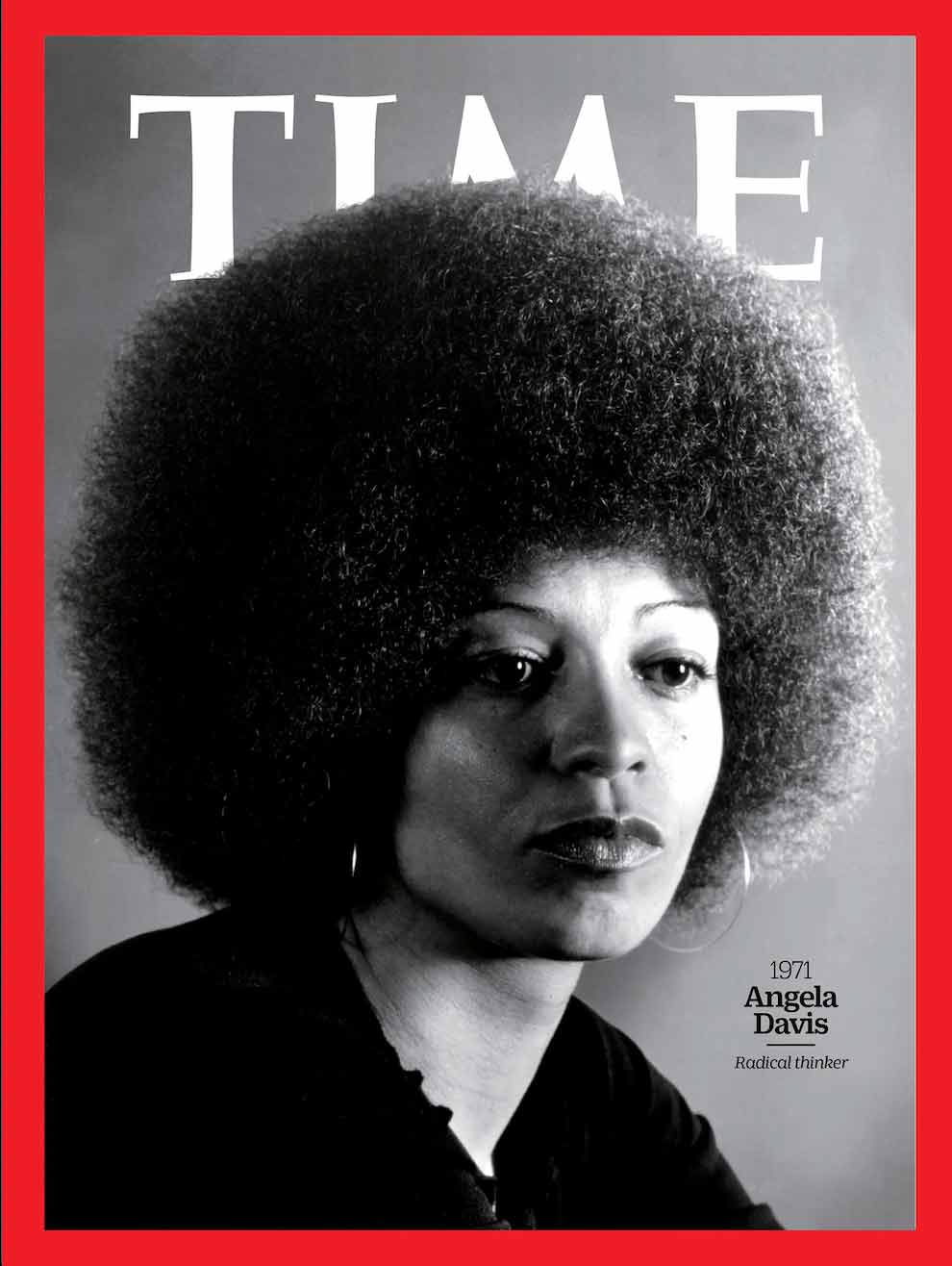

At that time, my ideal of feminine brilliance was Angela Davis. I embraced her ideas wholeheartedly; I admired her style. She, too, in her own way, was a kind of princess—one who dazzled as much through her words and actions as through her striking presence.

The years flowed on. I discovered Joe Zawinul, whom I would later cross paths with, just as I would Wayne Shorter. One might think that with time, passions wane, that affinities shift. But no—not really. If I were to tell you that today, the musicians who move me the most still come largely from the Black American community, it would be no exaggeration. Keb’ Mo’, Lakecia Benjamin, Kandace Springs, Michael Mayo, Christian McBride, Terri Lyne Carrington—the list is long, inexhaustible.

I still recall a music class where we listened to an ancient recording, a wax-cylinder capture from well before 1900. A voice, unmistakably that of a Black man, accompanied himself on a poorly tuned guitar, crying out more than he sang, “I’ve Got the Blues.” It was an experience that marked me profoundly. The anguish in his voice stirred my adolescent mind, already prone to intellectual musings. My curiosity ignited, I rushed to the school library, seeking anything that could illuminate the history of Black Americans—their struggles, their lives. But the only book I found was a French translation of Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

Reading it was nothing short of a trauma. It altered me, irrevocably. It reshaped my understanding of the world, much as the works of Marguerite Yourcenar, Paul Auster, and Mishima would in later years. Education is paramount. It is always the educated who carry the torch of justice, who lend their voices to the voiceless.

What sets Black American society apart is its singular ability to stir the conscience of the world through the arts. Otis Redding, Marvin Gaye, and so many others have carried this history in their music, guiding countless young Americans—and young Europeans, too—toward an understanding of the world, toward acceptance of the other, toward a rejection of injustice. I am merely an heir to that twentieth-century consciousness.

And today’s world? It fills me with sorrow. But still, I hold onto hope—that change, true and just, may come once more.

Thierry De Clemensat

USA correspondent – Paris-Move and ABS magazine

Editor in chief Bayou Blue Radio, Bayou Blue News

PARIS-MOVE, March 1st 2025

Follow PARIS-MOVE on X

::::::::::::::::::::::

Black History Month on PBS.org

Black History Month on History.com

Black History Month on Kids.NationalGeographic.com