| World Jazz |

In an era when global migration continually reshapes the American cultural landscape, certain musicians emerge not just as performers but as interpreters of identity, artists who transform displacement, hybridity and memory into sound. Among them, it is tempting, perhaps even unavoidable, to draw a line between Wanees Zarour and Juan Carmona, two artists separated by geography yet bound by an instinctive, string-borne language. Zarour with his oud and Carmona with his flamenco guitar both tap into traditions that refuse to be contained by borders, producing music that feels less like a fusion and more like a dialogue carried across centuries. Their flamenco-tinged jazz, brushed with Arab melodic sensibilities, speaks the way great art so often does: as a reminder that identity, fully inhabited, has a way of asserting itself even in a world determined to smooth its edges.

To understand Zarour’s work is to recognize the power of heritage in diasporic spaces. For him, Palestinian culture is not a theme to be evoked but a living pulse at the center of his artistry. His music becomes, almost inevitably, a torch extended toward those who would rather see that flame extinguished, a demonstration that cultural memory, once anchored, is not easily erased. In the United States, where he has lived for years, Zarour has crafted a language that merges tradition with an elegance shaped by classical discipline, modal scholarship, and a sensibility sharpened by global influence. His command of Western classical music does more than broaden his palette; it deepens the narrative architecture of his work, giving it an intellectual and emotional weight that resonates across borders.

Born into a family of musicians, Zarour entered the world of classical violin at age seven at the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music. He advanced quickly, absorbing the repertoire with the kind of discipline more often associated with prodigies. But what ultimately set his trajectory was immersion in the maqam system, the modal and philosophical core of Arabic music. He studied the Arabic violin tradition, Middle Eastern rhythms, and the structural forms that give the region’s music its hypnotic, spiraling architecture. Under the guidance of master musicians, he expanded his instrumentarium: oud, percussion, and especially the buzuq, the long-necked lute that would eventually reveal him as a virtuoso of rare agility.

Today, in Chicago, Zarour channels those formative years into a broader communal project. As director of the University of Chicago’s Middle East Music Ensemble, he has shaped a 70-member orchestra that performs Turkish, Arab, and Persian repertoire to packed halls. He arranges and transcribes every work, curating concerts designed not simply to present music but to cultivate dialogue, across cultures, across generations, across histories that rarely get to speak to one another so directly. In rehearsal, he is known not just for precision but for generosity: pausing to explain a rhythmic cycle, demonstrating an ornament, urging musicians who have never encountered maqam to “feel the phrase rather than count it.”

Yet to imagine Zarour’s music as anchored solely in tradition would be to misunderstand the breadth of his vocabulary. The jazz dimension, subtle, organic, and structurally integrated, gives his compositions a fluidity rarely found in contemporary world music. His work sits comfortably in the lineage of world-jazz pioneers, artists who used improvisation not to escape their cultural origins but to expand them. Joe Zawinul comes immediately to mind: a musician whose global sensibility redefined jazz without diluting the traditions he drew from. And indeed, there are passages in Zarour’s new album that recall the shimmering textures of Weather Report, moments where rhythmic intricacy and modal improvisation intertwine with a freedom that feels at once intimate and cosmic.

Zarour’s oud playing, too, reveals this dual inheritance. There are turns of phrase, rasgueado-like bursts, rapid arpeggiated entrances, that evoke flamenco guitar, tethering him, if only through resonance, to musicians like Juan Carmona. The connection is not accidental. Flamenco’s history is inseparable from the musical traditions of North Africa and the Middle East; its cadences, its microtonal inflections, its fiery emotional atmosphere are the remnants of centuries-long exchanges that defy national narratives. To place Zarour and Carmona side by side, then, is not to propose a fusion but to illuminate a shared ancestry, a long echo of cultural migrations that left fingerprints across both shores of the Mediterranean.

One could even argue that Zarour and Carmona operate as parallel cartographers, mapping not territories but emotional geographies where identity is porous, adaptive, and fiercely alive. In this context, Zarour’s album becomes more than a collection of pieces; it forms a statement about cultural endurance. At a moment when Palestinian lives, narratives, and histories remain under constant threat, his music asserts itself as a form of artistic resistance, not militant, but resolute; not rhetorical, but profoundly human.

Still, none of this would matter if the music itself did not stand on its own. And this album does. If 2026 is destined to open with a wave of strong releases, Zarour’s contribution is among those that demand to be kept close, the kind of record that insists on repeat listening. Its seven original compositions unfold like chapters in a novel, each distinct, each layered, each revealing something new with every encounter. The orchestrations are intricate without being dense; the rhythmic structures complex yet never overwrought. There are moments of ecstatic intensity, where the ensemble surges with a force that feels cinematic. There are passages of delicate poetry, where the oud seems to whisper rather than speak. And there are romantic interludes, understated yet strikingly emotional.

It took multiple listens to trace the album’s architecture, its shifting time signatures, its subtle thematic recalls, its unexpected harmonic pivots. But that is precisely its strength: an originality that rewards patience and invites discovery. This is not background music; it is a work that asks something of the listener, attention, openness, curiosity, and gives back something larger in return.

In the end, Wanees Zarour offers more than a musical experience. He offers a reminder that identity, when carried with clarity and conviction, becomes an artistic force that transcends borders and survives erasure. His music speaks to a world in which cultural memory is contested terrain—and yet, in the hands of artists like him, remains profoundly, defiantly alive.

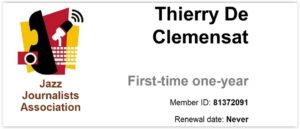

Thierry De Clemensat

Member at Jazz Journalists Association

USA correspondent for Paris-Move and ABS magazine

Editor in chief – Bayou Blue Radio, Bayou Blue News

PARIS-MOVE, November 25th 2025

Follow PARIS-MOVE on X

::::::::::::::::::::::::

Musicians:

Wanees Zarour, buzuq, oud, percussion

Sammuel Moshing, guitar

Andrew Lawrence, piano, keyboard

Vinny Kabat, bass

Bryan Pardo, saxophone, clarinet

Catie Hickey, trombone

Nick Kabat, drums

Taraq Rantisi, percussion

Track Listing:

Silwan

Lifta

Autumn

Festival

Fig Tree

Cold City

Anthem