| Jazz |

David Bode steps into the spotlight, following in the footsteps of Trombone Shorty — New Orleans, once again, takes center stage.

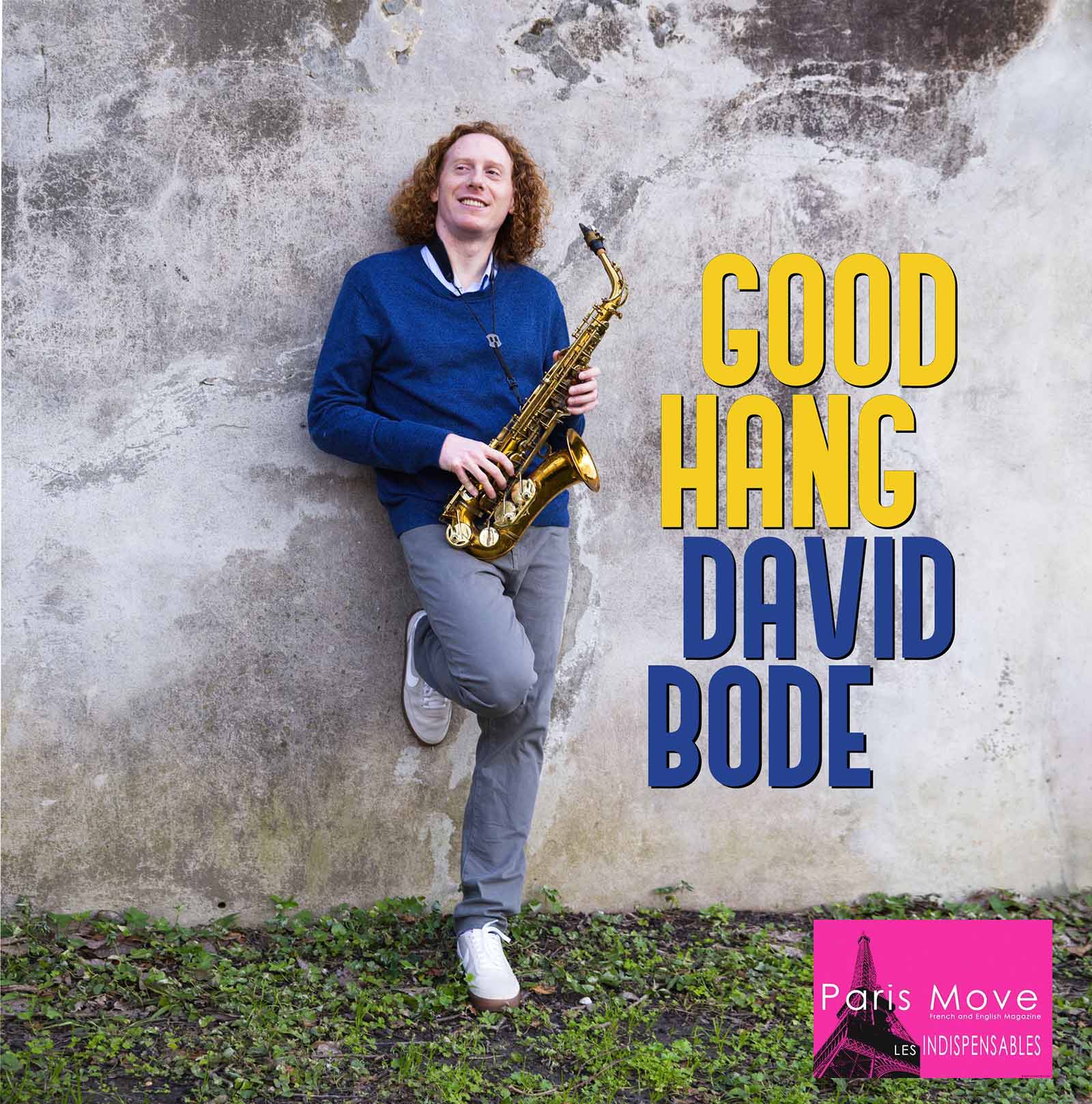

There are few cities in the world where music feels less like an art form and more like a civic necessity. New Orleans, that storied cradle of jazz, brass bands, second lines, and funk, has given birth to so many musical voices that any newcomer has to fight to be heard. To thrive in this landscape requires more than technical prowess. It demands originality, authenticity, and a kind of fierce joy that can cut through the noise. Saxophonist and composer David Bode, with his debut album Good Hang, manages exactly that, presenting a body of work that feels both reverent to his hometown’s traditions and refreshingly unconcerned with simply repeating them.

From the opening notes, Bode’s music suggests a kinship with the greats of his city. There is the structural sophistication and disciplined lyricism that recalls the Marsalis family, paired with the swagger and showmanship of Trombone Shorty, whose career has embodied the modern, genre-crossing face of New Orleans brass. And yet Bode avoids being derivative. Instead, he emerges as a kind of “missing link,” not an imitator but an artist in dialogue with these figures, someone who channels both traditions without being defined by them.

The centerpiece of Good Hang is the David Bode Big Band, which operates less like a museum piece of swing nostalgia and more like a living, breathing organism. His arrangements are expansive, often cinematic, overflowing with tonal colors that conjure Technicolor vistas. Listening, one has the impression of a composer who doesn’t so much write charts as sketch storyboards. Each track unfolds like a scene: brash brass fanfares exploding across the stereo field, reeds weaving intricate countermelodies, rhythm sections alternately propulsive and restrained. This is orchestral jazz that revels in scale, but never loses sight of detail.

One of the most striking moments arrives with Bode’s reinterpretation of Piazzolla’s “Libertango.” In lesser hands, Piazzolla can become either overwrought or politely academic. Bode sidesteps both traps, infusing the piece with humor, rhythmic daring, and a cosmopolitan spirit. It is at once playful and profound, respectful of the tango’s DNA yet restless enough to make it swing in ways Piazzolla himself might have admired. It also signals something essential about Bode’s worldview: his refusal to be bound by geography or genre.

Indeed, Good Hang constantly gestures outward. While grounded in the grooves of New Orleans, those second-line syncopations and gospel-tinged cadences that make the city’s music instantly recognizable, the record wanders into world-music textures, global rhythms, and melodic palettes that feel as much international as local. This is not a retreat from New Orleans identity, but rather an assertion that the Crescent City’s spirit has always been about absorption, exchange, and reinvention.

That perspective was forged over decades. Bode’s biography reads like a case study in musical hybridity: raised on a diet that included the Meters and Professor Longhair alongside the Louisiana Philharmonic and his parents’ rock-and-R&B vinyl, he is the product of both street parades and symphony halls. His formal training at Loyola University and the University of New Orleans put him under the tutelage of respected educators like Tony Dagradi and Johnny Vidacovich, but his education was equally in the clubs, festivals, and rehearsal rooms where he played with ensembles ranging from the New Orleans High Society to the New Leviathan Oriental Foxtrot Orchestra. These experiences honed not just his technique but his ability to navigate wildly different traditions, a skill audible in every track of Good Hang.

And then there is the matter of timing. The album’s release, twenty years to the day after Hurricane Katrina and the catastrophic levee failures, casts an unavoidable shadow. Bode himself acknowledges this marker with both humility and gravity. “My family was very fortunate with Katrina,” he reflects. “But it was the first time I had been away from Louisiana for months, and it left a lasting mark on me. When I returned, I felt once again how essential New Orleans is to the history of music. This album is the culmination of many years of study, performance, writing, and living. My hope is that my contribution to New Orleans’s musical story will resonate with listeners everywhere.”

The sentiment is telling. Good Hang is not an album preoccupied with mourning or nostalgia, but it does carry the weight of history. It is a work born of a city that knows survival, that transforms loss into art and resilience into rhythm. Katrina, in this sense, is not just an event in Bode’s past but part of the larger cultural inheritance of New Orleans musicians, a reminder of why making music here is never just personal but communal.

Critically, the album succeeds because it balances ambition with accessibility. Its arrangements are sophisticated without being forbidding, intricate without losing groove. There is virtuosity on display, but never at the expense of soul. Even in its boldest detours, the Piazzolla reimagining, the nods to world-music traditions, the music remains anchored in a kind of generosity, a desire to bring listeners along rather than intimidate them.

In a city where competition for attention is fierce, Bode has carved out a place not by emulating but by reimagining. His vision of a big band is not a retro exercise but a forward-looking laboratory, one that points toward a more globalized, kaleidoscopic jazz. Good Hang suggests that his role in New Orleans’s ongoing musical conversation is only just beginning.

And so, while Trombone Shorty may remain the face of the city’s youthful brass exuberance, and the Marsalis clan the emblem of its formal refinement, David Bode emerges as something different, a cosmopolitan connector, a curator of influences, and, above all, a storyteller in sound. His debut not only contributes to New Orleans’s cultural legacy but expands it, offering a vision of jazz that is proudly rooted yet unmistakably global.

In a city that has always blurred the lines between the local and the universal, that feels exactly right.

Thierry De Clemensat

Member at Jazz Journalists Association

USA correspondent for Paris-Move and ABS magazine

Editor in chief – Bayou Blue Radio, Bayou Blue News

PARIS-MOVE, August 19th 2025

Follow PARIS-MOVE on X

::::::::::::::::::::::::

Musicians :

David Bode – Alto & Soprano Sax, Flute (solo: 6, 8)

Lori LaPatka – Alto & Soprano Sax

Ari Kohn – Tenor Sax, Flute (solo: 3)

Byron Asher – Tenor Sax, Bb & Bass Clarinet (solo: 2, 5)

Thad Scott – Bari Sax, Flute (solo: 9)

Michael Joseph Christie – Trumpet & Flugelhorn (Solo: 2)

Mike Kobrin – Trumpet & Flugelhorn (Solo: 7)

Jonathan Bauer – Trumpet & Flugelhorn (1st Solo: 1)

Matt Perronne – Trumpet & Flugelhorn (Solo: 8)

John Zarsky – Trumpet & Flugelhorn (2nd Solo: 1)

Peter Gustafson – Trombone (Solo: 5)

Evan Oberla – Trombone (Solo: 6)

Jeff Albert – Trombone (Solo: 1)

Ethan Santos – Trombone (Solo: 2)

Jimmy Williams – Sousaphone

Daniel Meinecke – Piano, Rhodes, Organ (Solo: 4)

Eric Merchant – Guitar (Solo: 7)

Calvin Morin-Martin – Acoustic & Electric Bass (Solo: 3)

Ronan Cowan – Drums (Solo: 7)

Track Listing:

- Syeeda’s Song Flute (J. Coltrane) 5:14

- Libertango (A. Piazzola) 8:15

- Spring Can Really Hang You Up The Most (F. Landesman/T. Wolf) 9:29

- Happy People (K. Garrett) 7:08

- Lover, You Should’ve Come Over 9:44 (J. Buckley)

- Cold Train Funk (D. Bode) 7:34

- Monkey Puzzle (J. Black) 5:58

- Temporary Blindness (D. Bode) 8:22

- Dear Prudence/Don’t Let Me Down (J. Lennon/P. McCartney) 7:23